COMBAHEE RIVER COLLECTIVE ZINE

for my final project in my queer theory course, i took the opportunity to learn more about the Combahee River Collective - a really rad Black lesbian feminist collective that was active in the mid 70’s through early 80’s.

you can read it all below, or - click here to download the zine as a print-friendly version (with printing and folding instructions on the last page). feel free to print it out, distribute it, use the info to create your own resources, etc!

For accessibility and easy copy/pasting, here are the full written contents + image descriptions:

front cover

text reads:

the COMBAHEE RIVER COLLECTIVE: an introductory zine!

page description:

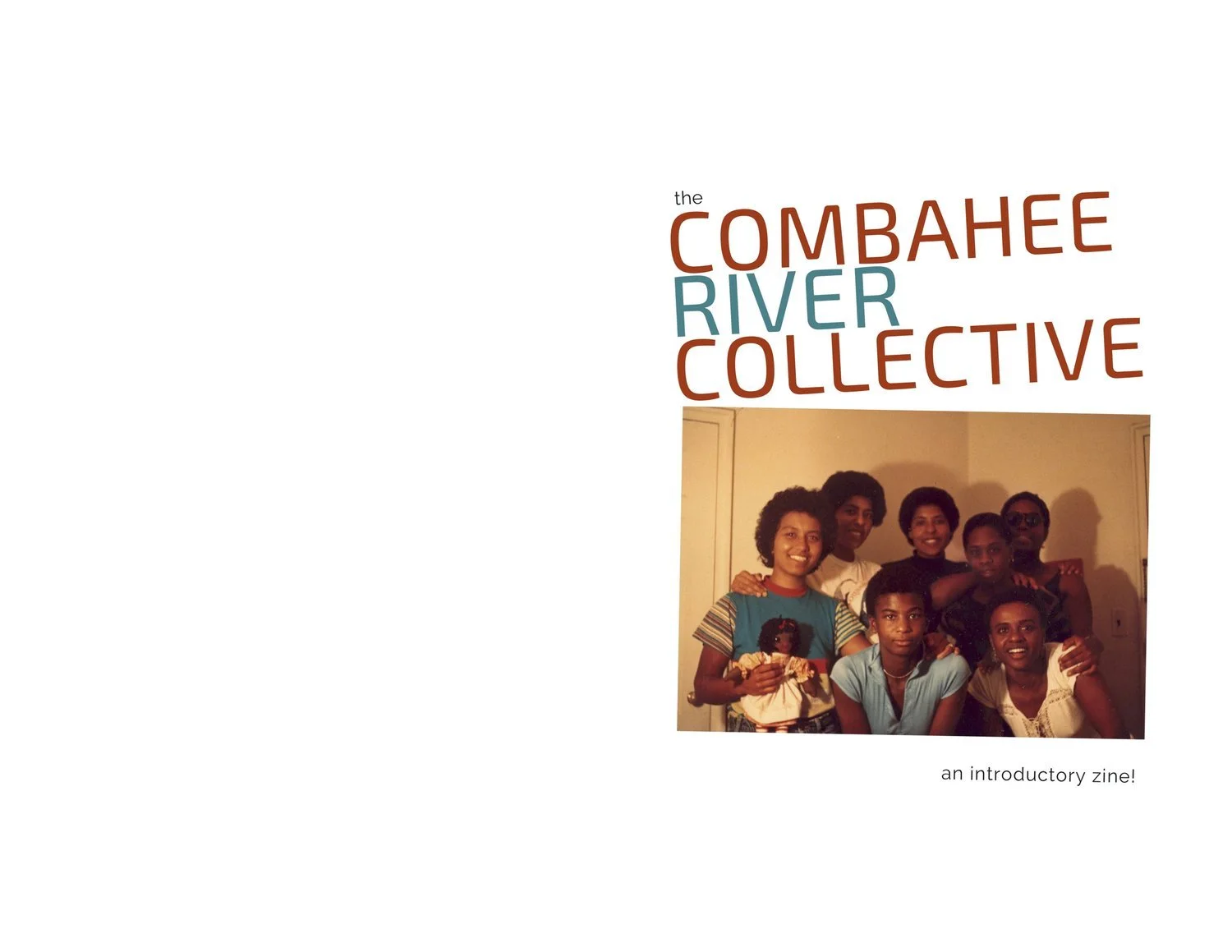

large text in red and blue, above a color photo from a Combahee River Collective retreat in 1977. back left to right are: Margo Okazawa-Rey, Barbara Smith, Beverly Smith, Chrilane McCray & Mercedes Tompkins. front left to right are: Demita Frazier & Helen Stewart.

inside cover

text reads:

zine assembled may 2021. please copy / share / distribute this zine!

page description:

text is scattered around the page, along with a black and white candid photo of Barbara Smith, Beverly Smith, & Demita Frazier, who are all smiling and laughing. (there are also image captions for the front and back covers on this page, but I just put that info with those pages).

contents page

text reads:

zine contents: basics + timeline … pg 1, key terms + concepts … pg 2, history … pg 3, framework … pg 5, members + contributors … pg 7, their statement … pg 9, legacy … pg 13, resources + "How We Get Free … pg 15.

page description:

below the contents list is a black and white photo of CRC member Barbara Smith on the megaphone at a protest following the murders of nine (a number which later rose to twelve) young Black women who were believed to be sex workers, which occurred in Boston over just a few months, in 1979. Other members stand around and behind her, with signs that say things like: “NOT ANOTHER BLACK WOMAN KILLED”.

page 1

text reads:

basics + timeline: The Combahee River Collective (CRC) was a collective of Black lesbians who were active from 1974-1980. They were anti-racist, anti-capitalist, anti-colonial, and anti-imperial, and drew on Black Marxist and Black-Nationalist movements; but applied their Black feminist lens to this work, creating a much needed space for Black, queer, and working class women who were excluded from 2nd wave feminism's focus on white middle class women, and the male dominance present in Black-nationalist orgs.

page description:

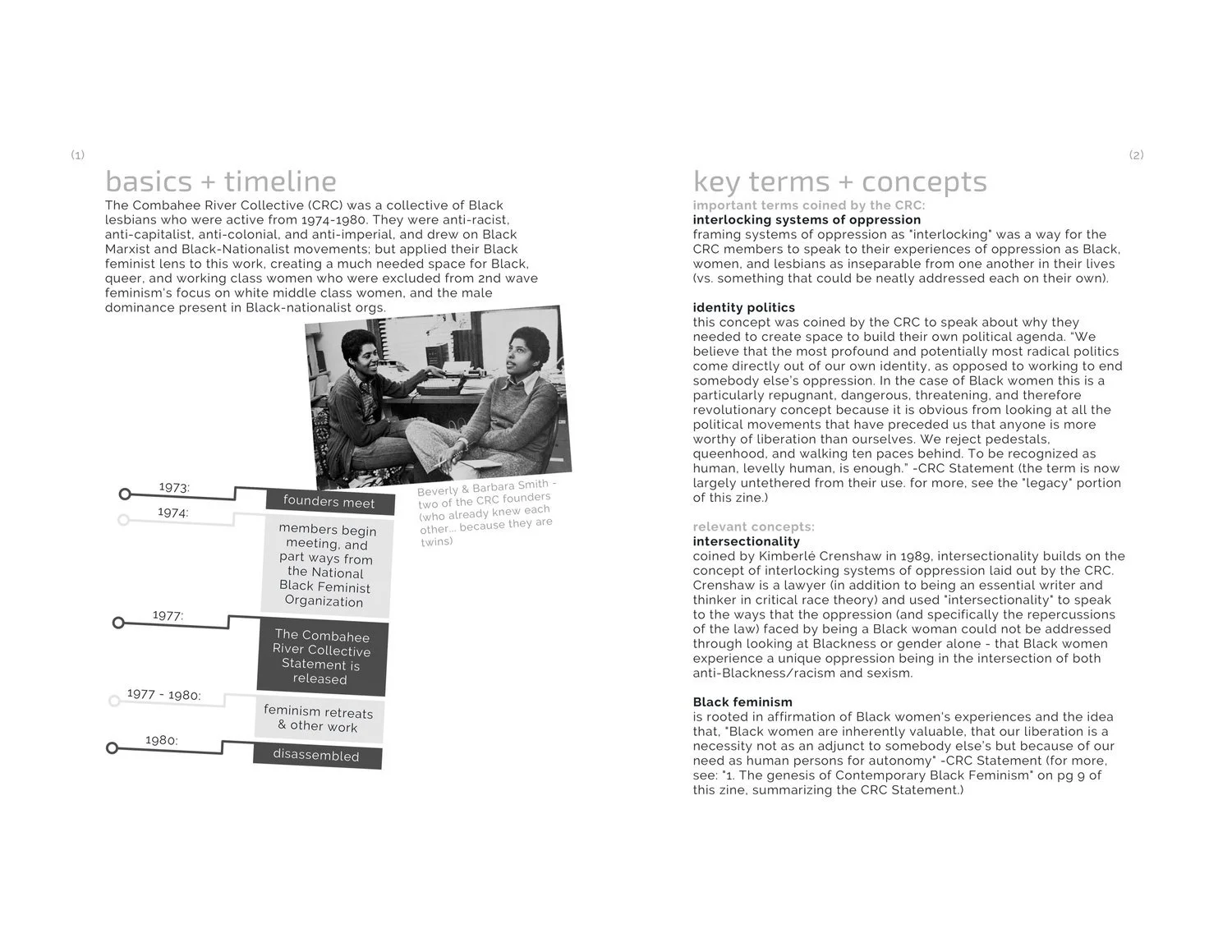

Below the text is a black and white photograph of Beverly & Barbara Smith - two of the CRC founders, who are also twins. They’re sitting together at a desk, Beverly smiling with her hand on a typewriter, and Barbara looking up as if in mid-thought. There is also a timeline which reads: 1973: founders meet, 1974: members begin meeting, and part ways from the National Black Feminist Organization, 1977: The Combahee River Collective Statement is released, 1977-1980: feminism retreats & other work, 1980: disassembled.

page 2

text reads:

key terms + concepts: important terms coined by the CRC: interlocking systems of oppression: framing systems of oppression as "interlocking" was a way for the CRC members to speak to their experiences of oppression as Black, women, and lesbians as inseparable from one another in their lives (vs. something that could be neatly addressed each on their own). identity politics: this concept was coined by the CRC to speak about why they needed to create space to build their own political agenda. “We believe that the most profound and potentially most radical politics come directly out of our own identity, as opposed to working to end somebody else’s oppression. In the case of Black women this is a particularly repugnant, dangerous, threatening, and therefore revolutionary concept because it is obvious from looking at all the political movements that have preceded us that anyone is more worthy of liberation than ourselves. We reject pedestals, queenhood, and walking ten paces behind. To be recognized as human, levelly human, is enough.” -CRC Statement (the term is now largely untethered from their use. for more, see the "legacy" portion of this zine.) relevant concepts: intersectionality: coined by Kimberlé Crenshaw in 1989, intersectionality builds on the concept of interlocking systems of oppression laid out by the CRC. Crenshaw is a lawyer (in addition to being an essential writer and thinker in critical race theory) and used "intersectionality" to speak to the ways that the oppression (and specifically the repercussions of the law) faced by being a Black woman could not be addressed through looking at Blackness or gender alone - that Black women experience a unique oppression being in the intersection of both anti-Blackness/racism and sexism. Black feminism: is rooted in affirmation of Black women's experiences and the idea that, "Black women are inherently valuable, that our liberation is a necessity not as an adjunct to somebody else’s but because of our need as human persons for autonomy" -CRC Statement (for more, see: "1. The genesis of Contemporary Black Feminism" on pg 9 of this zine, summarizing the CRC Statement.)

page description:

this page is just text.

page 3

text reads:

history: The CRC founders first met in 1973 at a regional conference for the National Black Feminist Organization (NBFO). They began meeting regularly in Cambridge, MA in 1974, and parted ways from the NBFO (which they supported but felt was not radical enough to affect the social change they wanted for themselves and their communities) - to define their own politics, rooted in a Black feminist lens. The collective was named (at the suggestion of one of the co-founders, Barbara Smith) for the Combahee River raid of 1863. The operation was led by Harriet Tubman, and 750+ enslaved people were freed. It is considered the only US liberatory military strategy designed and led by a woman - which situated the CRC in a history of Black women doing radical liberatory work. They are best known for their 1977 statement, but they were also active in the desegregation of Boston public schools, had community campaigns against police brutality in Black neighborhoods, stood in solidarity in picket lines demanding construction jobs for Black workers, were active in raising visibility around issues of violence against Black women and sex workers (particularly in 1979, re: a string of racially and sexually motivated murders in Boston which were largely ignored by the media), and were involved in an initiative to stop Black and Brown women from being sterilized against their wills. From 1977-1980 they ran seven feminism retreats, which involved 1000's of women - who had often been doing liberatory and justice work in isolation - to share resources, ideas, and support.

page description:

Below the text is an 1863 illustration of the Combahee River raid. It is black and white and shows enslaved people being rescued, with riverboat fires in the background.

page 4

page description:

This page has various black and white photographs of CRC pamphlets, which were used to raise awareness about the 1979 murders - which had to be regularly updated as more women were killed, and therefore have edits such as the “SIX” in “SIX BLACK WOMEN WHY DID THEY DIE?” crossed out to be changed to “7”, then “8”, then “ELEVEN”.

page 5

text reads:

framework: The need to form the CRC rose from the centering of white, middle class women in 2nd wave feminism, and a refusal of white feminist groups to expand their focus beyond specific issues (that they were directly affected by) to a broader, multi-pronged frameworks centering those most affected by the matrix of domination. “In the reality of organizing, these tensions manifested themselves in white women’s desire to focus their organizing on abortion rights, while Black feminists argued for the broader framework of reproductive justice, which included the struggle against forced sterilizations of Black and brown women. These were hardly doctrinaire disputes” - Keeanga-Yamahtta Taylor, 2020. It was also necessary to create a space where the issues affecting Black women were centered - and this meant building space outside of the male dominance of many Black-Nationalist orgs (Demita Frazier, one of the founding members, was a former Black Panther Party member). “If Black women were free, it would mean that everyone else would have to be free since our freedom would necessitate the destruction of all the systems of oppression.” - CRC Statement, 1977. CRC rejected lesbian separatism and stood for solidarity and coalition building between people affected by racial, sexual, heterosexual, and class oppression: “Although we are feminists and Lesbians, we feel solidarity with progressive Black men and do not advocate the fractionalization that white women who are separatists demand. Our situation as Black people necessitates that we have solidarity around the fact of race, which white women of course do not need to have with white men, unless it is their negative solidarity as racial oppressors. We struggle together with Black men against racism, while we also struggle with Black men about sexism.” - CRC Statement, 1977.

page description:

this page is just text.

page 6

page description:

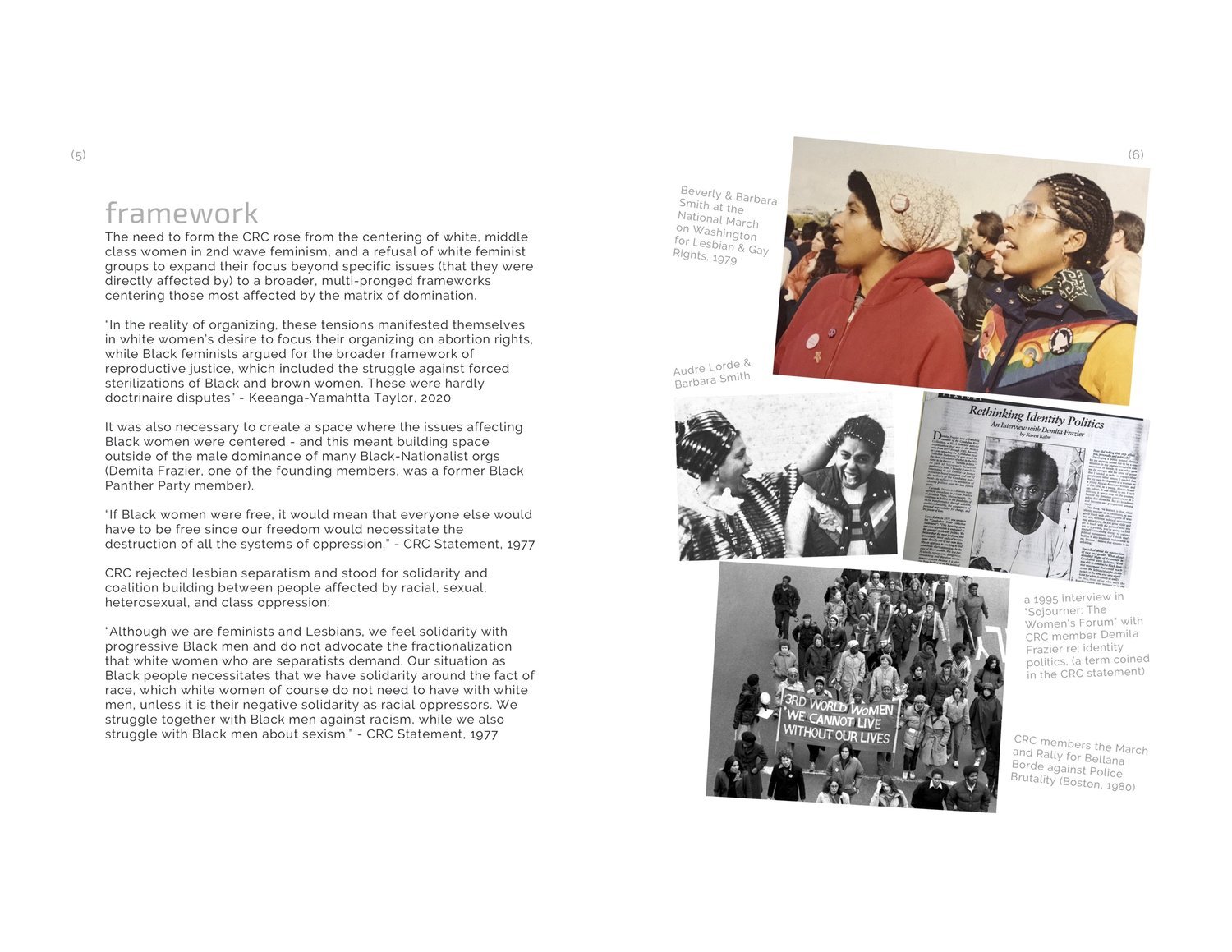

Various photos and captions are scattered around the page. They are: a color photograph of Beverly & Barbara Smith at the National March on Washington for Lesbian & Gay Rights, 1979 - they both have really great outfits with pins on them - Barbara’s vest is especially good and has a rainbow V pattern on the front. A black and white photo of Audre Lorde and Barbara Smith - Barbara is smiling and shouting while Audre grabs her braided hair. A newspaper page featuring a 1995 interview in "Sojourner: The Women's Forum" with CRC member Demita Frazier re: identity politics, (a term coined in the CRC statement), and an overhead photo from a the March and Rally for Bellana Borde against Police Brutality (Boston, 1980) where CRC members can be seen holding a banner that reads “3RD WORLD WOMEN WE CANNOT LIVE WITHOUT OUR LIVES”.

page 7

text reads:

members + contributors: CRC Founders & primary authors of the CRC Statement: Barbara Smith: @TheBarbaraSmith on twitter // barbarasmithaintgonna.com Barbara has made significant contributions to Black feminism, including her 1977 essay, “Toward a Black Feminist Criticism". Following her work with the CRC, Barbara was a leader in establishing the field of Black women's studies in the US. She also co-founded one of the first independent presses in the US committed to publishing the work of women of color, and has worked in public office and on urban policy. Beverly Smith: Beverly is an instructor of Women's Health at the University of MA Boston. Her work on women's health, racism, feminism, and identity politics have been published extensively. Demita Frazier: demitafrazier.com Prior to her work with CRC, Demita was an organizer behind the Chicago Black Panther Party's Breakfast Program, and has been involved in many other projects including work on: reproductive rights, domestic violence, the care and protection of children, urban sustainability issues affecting food access in poor and working class communities. She defines her current life goals as: avid participation in the ongoing project of dismantling the myth of white supremacy, ending misogynoir, hetero-patriarchal hegemony, and undermining late stage capitalism, with the hope of joining with others in creating a democratic socialist society. Margo Okazawa-Rey: aaww.org/on-the-radical-possibilities-of-leading-with-love-an-interview-with-dr-margo-okazawa-rey/ Margo's work with the CRC informed her scholarship and activism that followed, centered primarily around military violence against women, inter/intra-ethnic conflicts, and critical multicultural education. She was previously a professor in multiple women's leadership and studies programs.

page description:

this page is just text.

page 8

text reads:

The CRC was not small or static, so this is by no means comprehensive, but some other key members and contributors included: Akasha Hull: During her time as a member of the CRC, Akasha co-edited "All the Women Are White, All the Blacks Are Men, But Some of Us Are Brave: Black Women's Studies", which was essential to the development of Black women's studies. Her writing (including poetry) has been widely published. Chirlane McCray: After her time as a member of the CRC, Chirlane moved to NYC and became involved in politics - she has worked as a speechwriter, public affairs specialist, and for her husband Bill de Blasio's campaigns (as with the rest of the CRC members, she identified as a lesbian in the 70's. In 2013 she stated that she "hates labels"). She has published both poetry and essays. Audre Lorde: alp.org/about/audre In addition to being a member of the CRC, Audre was best known as an internationally known activist, artist, and poet. In a NYT piece Parul Sehgal states: "Her work is an estuary, a point of confluence for all identities, all aspects kept so strenuously segregated: poetry and politics, feeling and analysis, analysis and action, sexuality and the intellect". Cheryl Clark: blackwomenradicals.com/blog-feed/the-triumph-of-black-lesbian-feminist-resistance-honoring-radical-poet-and-activist-dr-cheryl-clarke Cheryl does not consider herself to have been a "member" of the CRC, but she participated in the retreats and was close with Barbara. She is a poet, essayist, educator, and co-owner of a rare books store. She has published four collections of poetry, and taught at Rutgers from 1970-2013 - where she also created co-curricular programming which made the university more accessible for students of color and queer students. Sharon Page Ritchie and Helen Stewart are also frequently cited as important contributors to the collective.

page description:

this page is just text.

page 9

text reads:

their statement: The CRC is perhaps best known for the Combahee River Statement - which was published in 1977. It was a unique document at the time, bringing together socialism and feminism - which were often framed as at odds with one another (for centering class and centering gender, respectively). The statement begins by situating their work as a collective, stating: "... we are actively committed to struggling against racial, sexual. heterosexual, and class oppression, and see asour particular task the development of integrated analysis and practice based upon the fact that the major systems of oppression are interlocking". The statement itself is not long (and can be found many places online for free - one is listed in the resources section of this zine) and I highly recommend that folks just read it as it is written - but here is a breakdown of its four sections:

1. The genesis of a Contemporary Black Feminism:

acknowledges the newness of contemporary Black feminism, and its long roots in the struggle for "survival and liberation", particularly as "an adversary stance to white male rule".

contextualizes contemporary Black feminism as an "outgrowth" of the activism of Sojourner Truth, Harriet Tubman, Frances E. W. Harper, Ida B. Wells Barnett, and Mary Church Terrell, "and thousands upon thousands unknown".

speaks to 2nd wave feminism's whiteness and its refusal to see or honor the necessity of Black women in the work of feminism.

speaks to the specific experiences (identity politics!) of Black women, and how this is a natural root of contemporary Black feminism.

situates contemporary Black feminism: "The fact that racial politics and indeed racism are pervasive factors in our lives did not allow us, and still does not allow most Black women, to look more deeply into our own experiences and, from that sharing and growing consciousness, to build a politics that will change our lives and inevitably end our oppression. Our development must also be tied to the contemporary economic and political position of Black people".

page description:

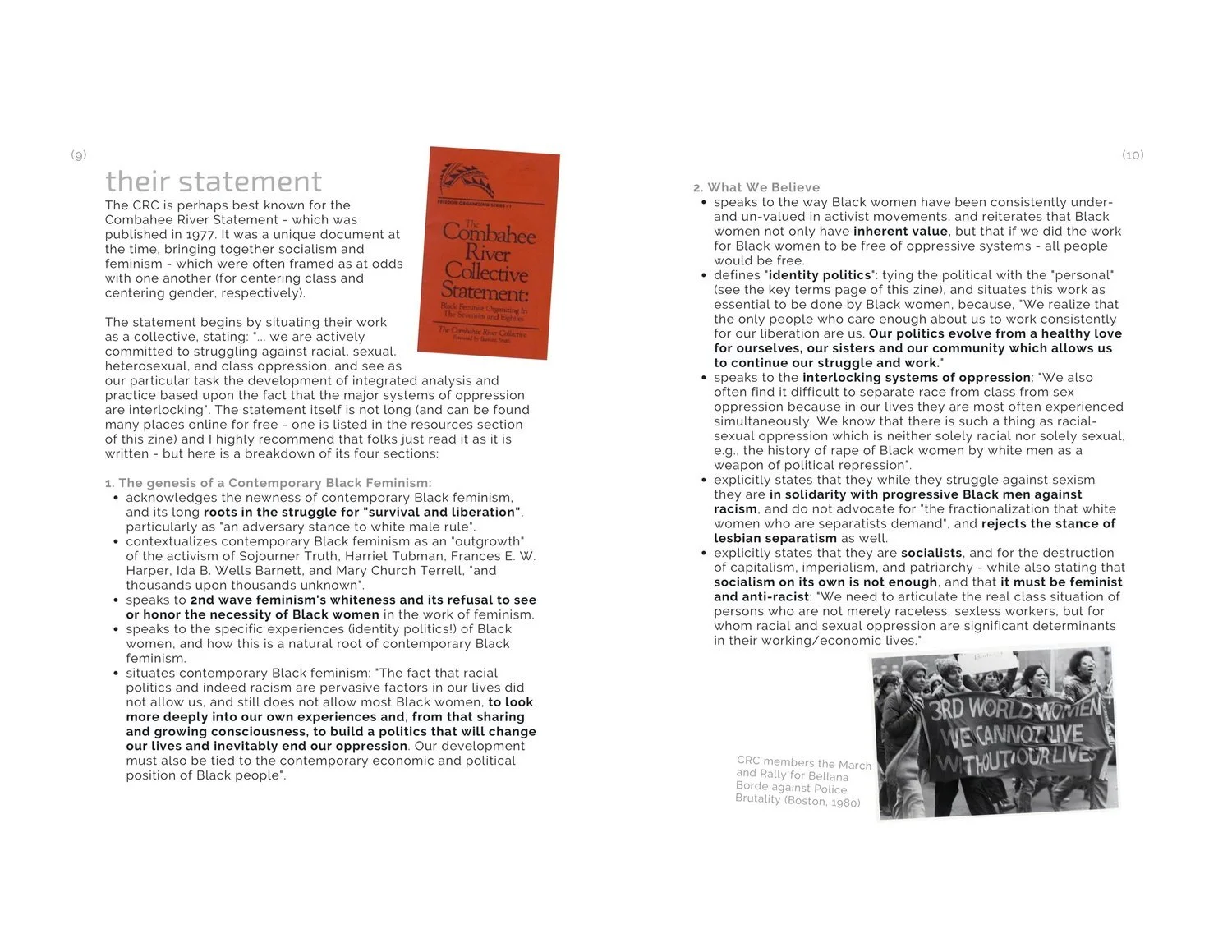

In the top right hand corner of the page is a photograph of a printed version of the statement, it is bright red.

page 10

text reads:

2. What We Believe

speaks to the way Black women have been consistently under- and un-valued in activist movements, and reiterates that Black women not only have inherent value, but that if we did the work for Black women to be free of oppressive systems - all people would be free.

defines "identity politics": tying the political with the "personal"(see the key terms page of this zine), and situates this work as essential to be done by Black women, because, "We realize that the only people who care enough about us to work consistently for our liberation are us. Our politics evolve from a healthy love for ourselves, our sisters and our community which allows us to continue our struggle and work."

speaks to the interlocking systems of oppression: "We also often find it difficult to separate race from class from sex oppression because in our lives they are most often experienced simultaneously. We know that there is such a thing as racial-sexual oppression which is neither solely racial nor solely sexual, e.g., the history of rape of Black women by white men as a weapon of political repression".

explicitly states that they while they struggle against sexism they are in solidarity with progressive Black men against racism, and do not advocate for "the fractionalization that white women who are separatists demand", and rejects the stance of lesbian separatism as well.

explicitly states that they are socialists, and for the destruction of capitalism, imperialism, and patriarchy - while also stating that socialism on its own is not enough, and that it must be feminist and anti-racist: "We need to articulate the real class situation of persons who are not merely raceless, sexless workers, but for whom racial and sexual oppression are significant determinants in their working/economic lives."

page description:

Below the text is a black and white photograph of CRC members at the March and Rally for Bellana Borde against Police Brutality (Boston, 1980), with the same banner as is in the photograph on page 6, but photographed from the ground, and in movement. Some of the women are smiling and some of them are chanting.

page 11

text reads:

3. Problems in Organizing Black Feminists

acknowledges that it has been difficult doing Black feminist organizing, and sometimes even just being present as an expressed Black feminist is exhausting or impossible.

some of the difficulties expressed include:

fighting a whole range of oppressions

not having privilege to rely upon

limited access to resources and power

the psychological toll of being a Black woman

isolation of Black women doing Black feminist work

feminism being a threat to some of the power dynamics in Black community and personal relationships

class and political differences

also acknowledges they ways in which they've been successful in organizing, and how far they'd come in just three years as a collective (from starting with no real direction, only a desire to create something that didn't exist and there was a need for)

lays out the direction they see their organizing moving in (at this time it was the plan to build study groups, to gather a collection of Black feminist writing, and to continue coalition-building).

4. Black Feminist Issues and Projects

lists both projects that the CRC has been actively involved in (such as: sterilization abuse, abortion rights, abuse, rape, health care, and education) and projects which would align with Black feminism (such as: workplace organizing, welfare, and daycare).

addresses racism in white feminism (as not the of Black feminists work to do, but work that must be continually demanded): "As Black feminists we are made constantly and painfully aware of how little effort white women have made to understand and combat their racism, which requires among other things that they have a more than superficial comprehension of race, color, and Black history and culture. Eliminating racism in the white women’s movement is by definition work for white women to do, but we will continue to speak to and demand accountability on this issue."

"We believe in collective process and a nonhierarchical distribution of power within our own group and in our vision of a revolutionary society. We are committed to a continual examination of our politics as they develop through criticism and self-criticism as an essential aspect of our practice."

page description:

this page is just text.

page 12

text reads:

Barbara Rasnby (comments via Socialism 2017 Conference, as shared in Keeanga-Yamahtta Taylor's "How We Get Free") : "If we take to heart the spirit and politics of the Combahee River Collective Statement, what we go away with is this: (1) never be afraid to speak truth to power, and (2) in the face of racist, misogynist threads of violence and attacks, when you have the impulse to either fight or flight, what do you do? Fight! And, (3) always ally yourself with those on the bottom, on the margins, and at the periphery of the centers of power. And in doing so, you will land yourself at the very center of some of the most important struggles of our society and our history".

page description:

Below the text is a photograph of Demita Frazier on the megaphone at a protest following the 1979 murders in Boston.

page 13

text reads:

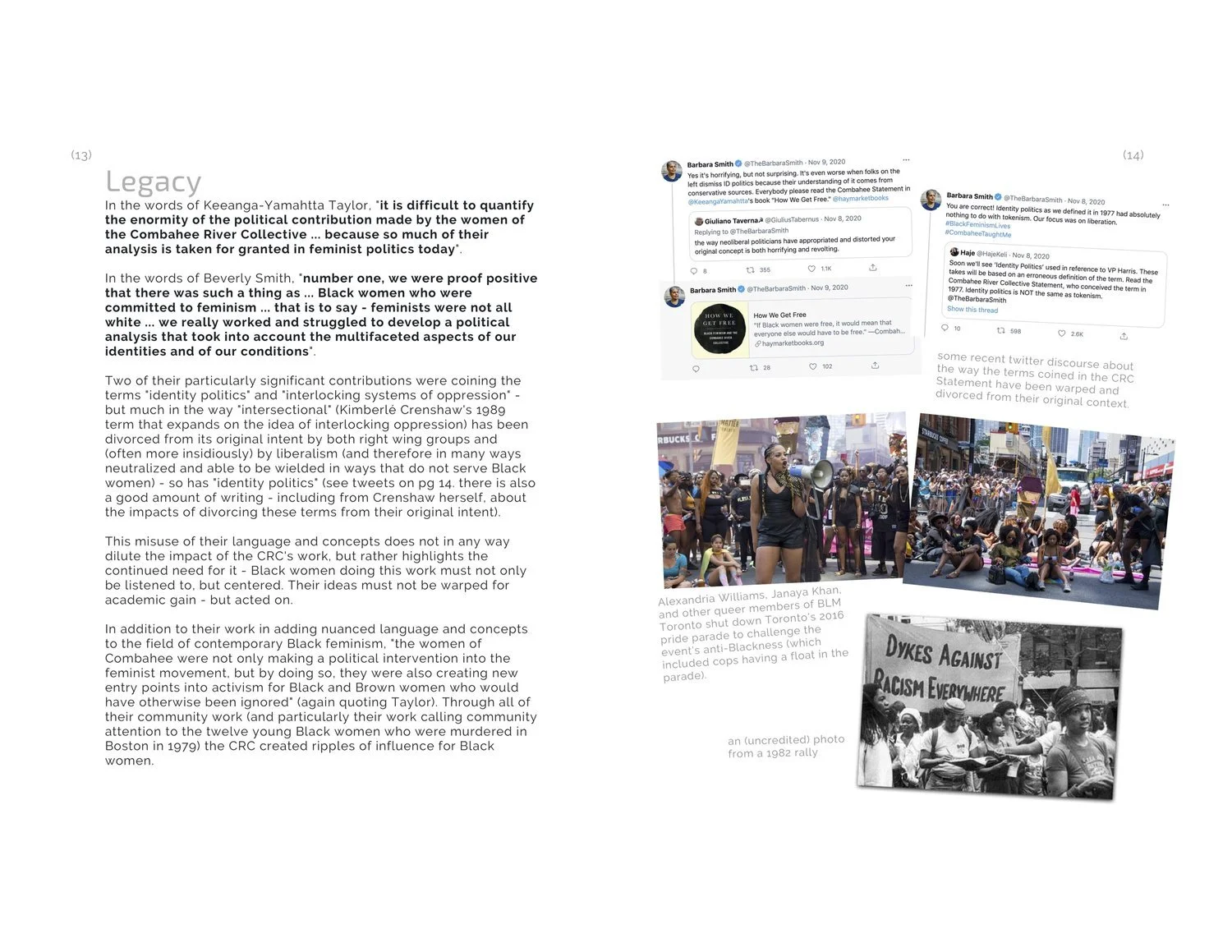

In the words of Keeanga-Yamahtta Taylor, "it is difficult to quantify the enormity of the political contribution made by the women of the Combahee River Collective ... because so much of their analysis is taken for granted in feminist politics today". In the words of Beverly Smith, "number one, we were proof positive that there was such a thing as ... Black women who were committed to feminism ... that is to say - feminists were not all white ... we really worked and struggled to develop a political analysis that took into account the multifaceted aspects of our identities and of our conditions". Two of their particularly significant contributions were coining the terms "identity politics" and "interlocking systems of oppression" - but much in the way "intersectional" (Kimberlé Crenshaw's 1989 term that expands on the idea of interlocking oppression) has been divorced from its original intent by both right wing groups and (often more insidiously) by liberalism (and therefore in many ways neutralized and able to be wielded in ways that do not serve Black women) - so has "identity politics" (see tweets on pg 14. there is also a good amount of writing - including from Crenshaw herself, about the impacts of divorcing these terms from their original intent). This misuse of their language and concepts does not in any way dilute the impact of the CRC's work, but rather highlights the continued need for it - Black women doing this work must not only be listened to, but centered. Their ideas must not be warped for academic gain - but acted on. In addition to their work in adding nuanced language and concepts to the field of contemporary Black feminism, "the women of Combahee were not only making a political intervention into the feminist movement, but by doing so, they were also creating new entry points into activism for Black and Brown women who would have otherwise been ignored" (again quoting Taylor). Through all of their community work (and particularly their work calling community attention to the twelve young Black women who were murdered in Boston in 1979) the CRC created ripples of influence for Black women.

page description:

this page is just text.

page 14

page description:

At the top of the page is a Twitter thread with tweets by Barbara Smith from November 2020 about the ways in which it is both horrifying and unsurprising that neoliberal politicians appropriate and distort the concept of identity politics, and how it is even worse when folks on the left “dismiss ID politics because their understanding of it comes from conservative sources”. She also links to Keenga-Yamahtta Taylor’s book “How We Get Free”. Below the Tweets are two color photographs of Alexandria Williams, Janaya Khan, and other queer members of BLM Toronto shut down Toronto's 2016 pride parade to challenge the event's anti-Blackness (which included cops having a float in the parade). Below those is an (uncredited) black and white photograph from a 1982 rally, Black folks gather in the street and a large banner behind them reads “DYKES AGAINST RACISM EVERYWHERE”.

page 15

text reads:

Resources: The following are sources that were used to assemble this zine, and/or places where you can learn more about the CRC, the folks in it, and its legacy:

read more about Combahee River Collective: blackpast.org/african-american-history/combahee-river-collective-1974-1980/

read the CRC Statement: blackpast.org/african-american-history/combahee-river-collective-statement-1977/

pages from one of the CRC pamphlets: Radical America vol. 13 no. 6: Black Feminism in Boston (pgs 42-51) library.brown.edu/pdfs/1124979008226934.pdf

related reading:

Until Black Women Are Free, None of Us Will Be Free: Barbara Smith and the Black feminist visionaries of the Combahee River Collective, Keeanga-Yamahtta Taylor (2020) newyorker.com/news/our-columnists/until-black-women-are-free-none-of-us-will-be-free

Black feminism and intersectionality, Sharon Smith (2013) isreview.org/issue/91/black-feminism-and-intersectionality

related videos/podcasts:

#ReadingRevolution - Left POCket Project Podcast spreaker.com/user/leftpoc/47-combahee-river-collective-statement-r

Democracy NOW: Keeanga-Yamahtta Taylor Interview: What We Can Learn From the Black Feminists of the Combahee River Collective youtube.com/watch?v=NfaNJ7ktIqA

page description:

this page is just text.

page 16

text reads:

How We Get Free: Another really rad resource is Keeanga-Yamahtta Taylor's 2017 book "How We Get Free: Black Feminism and the Combahee River Collective". The book includes an introduction from Taylor, interviews with Barbara, Beverly, and Demita of the CRC, an interview with Alicia Garza (a co-founder of BLM), and comments re: the 40th anniversary of the CRC Statement made by Barbara Ransby (a historian, writer, professor, and activist) - which notably warn against romanticizing the collective or their work. Keeanga-Yamahtta Taylor writes and speaks on Black politics, social movements, and racial inequality in the United States. She is a professor and award-winning/extensively published writer. Some of the most important work of the book is in the ways that it contextualizes the CRC Statement amidst recent history and events, including the 2016 presidential election (and the complexity/harm of what happened re: voting being placed on the shoulders of Black women), and the continued murders of Black people by the police. Taylor also pulls really incredible responses out of her interviewees, giving a lot of insight into what formed and impacted their individual politics, how these things showed up in the CRC's work, what felt significant in working with the CRC, and what they view its enduring contributions to Black feminism to be.

page description:

Below the text are two photographs, on the left is the book cover, which is off white with a Black watercolor circle in the center, and white text on top. On the right is a photo of Taylor, who is seated, leaning in a brown jacket and black cap, with a bookshelf behind her.

back cover

page description:

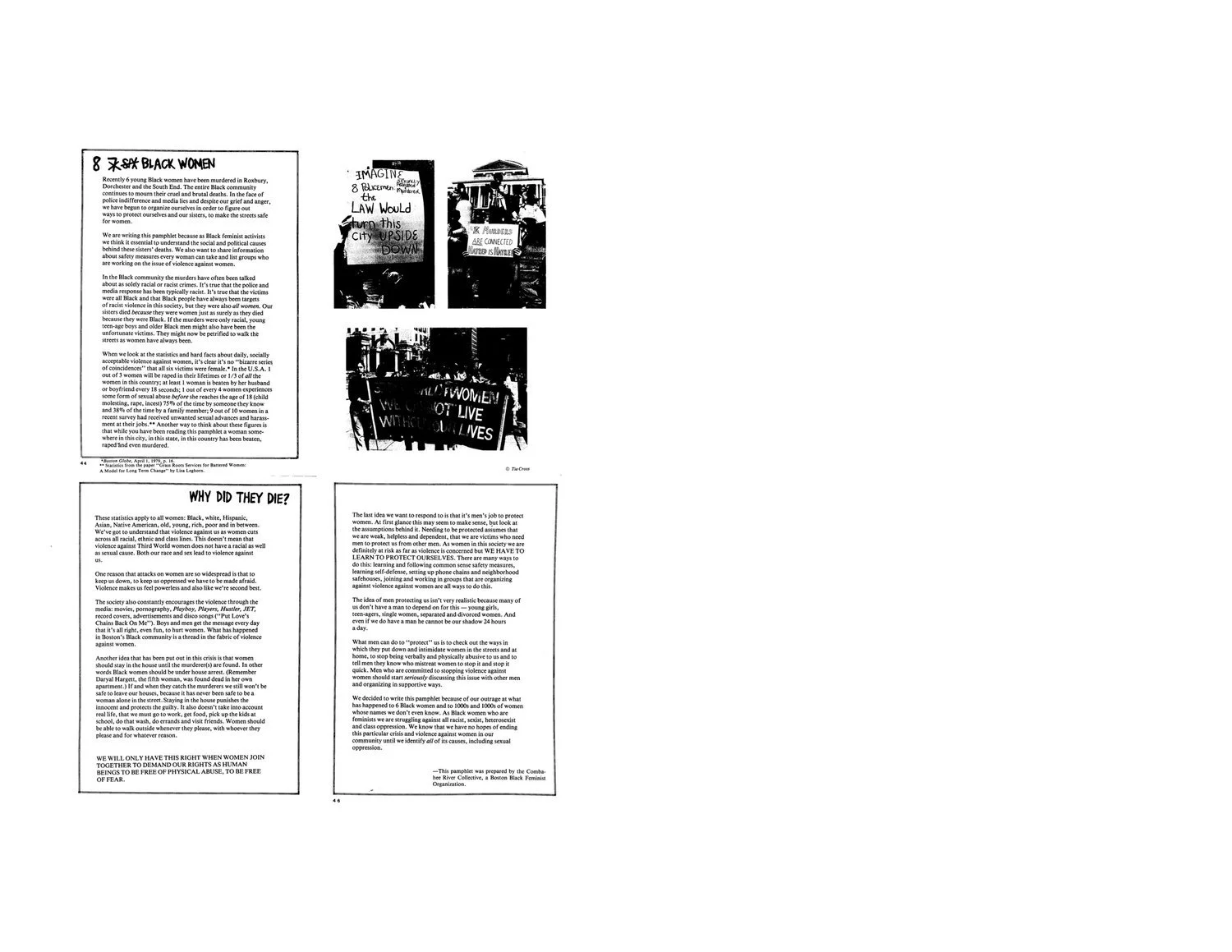

The back cover has 4 pages from one iteration of the Combahee River Collective's informational pamphlet (which also included suggestions for self-protection, and the poem "with no immediate cause" by Ntozake Shange) that was distributed in 1979 amongst the murders of twelve young Black women in Boston, MA. 26,000 copies were printed in English + 1000's in Spanish.